This year, my church, Daystar Christian Centre, turns 30.

And to witness my excitement as we countdown to the celebration, or if you saw me last Sunday as I excitedly took a photo of our billboard in Victoria Island, you would think I was a shareholder in the church.

I have been in the church 20 years now, since I was an undergrad at the University of Lagos.

And still now, having visited churches across the world and even after having preached on my church’s pulpit, I am still excited to go from the Island to Ikeja every Sunday to the same auditorium.

Because in church – in that church – I feel completely at home.

I feel safe.

I feel whole.

I feel loved.

That feeling, of belonging, of trust, of shared values, of spiritual continuity — is what drives faith in much of Nigeria and the continent.

It’s also why people happily give to temples, mosques, shrines, and churches — and keep giving even in hard times.

It’s why I continue to pay tithes to the church, excitedly, even when I know I don’t need to pay tithes to go to heaven or for God to bless me.

It’s not tax deduction.

It’s not brand equity.

It’s meaning.

Home is where the heart is.

To understand this connection, you have to understand the language of feeling, of connection, of emotion, of… faith.

Unfortunately when outsiders – by this I mean researchers, policymakers, NGO leaders, grant makers, conference attendees – try to interpret what I just said in a way that enables them make decisions, they miss the point.

They switch languages.

They start to atomize and to sterilize a feeling and experience that is alive and living; that penetrates “even to dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow”.

They design systems as if people are algorithms, not human beings with faith, fears, and emotions.

They design for economics and infrastructure; and thus they misunderstand and then mis-invest in the engines that shape behaviour, faith, film, and everyday storytelling.

But if we want durable social change in Africa; change that makes a real difference in the economics and well being of large numbers of people for long periods of time, then that needs to change.

⸻

According to our hosts today, across East, West, and Southern Africa, a review of 50 entertainment-based interventions found that only 46% produced positive shifts in social norms.

As someone who has worked across 21 African countries and helped presidents win elections and global companies sell software, I am not surprised of course; I am very familiar with this phenomenon.

When it comes to politics and business, those leaders are always ready to listen to reality. But when it comes to social change and advocacy, these other leaders routinely lose their grasp on reality. Because change makers and grantmakers and multilateral organizations often choose ideology over reality – refusing to align to how everyday Africans think and act.

• We copy Western playbooks and then wonder why behaviour doesn’t shift.

• We fund projects, not patterns.

• We split “service delivery” from “culture change,” when culture determines whether those services are adopted, resisted, or sustained.

• We ignore the obvious: that human beings routinely act against narrow economic self-interest if it conflicts with their inner values.

But if you don’t respect the story people tell themselves about reality, your funding and your attempts to help them will always fail.

⸻

You see the vast majority of the films, television series, concerts and content that donors fund to trigger social change, and you wonder if they don’t understand that that is not how the audience consumes.

You wonder how they miss that the voice and style of the Funke Akindeles and Kemi Adetibas are the ones that move audiences in this market, not the Euro-centric voices of filmmakers who excite film reviewers in Toronto, but are completely ignored by the audience in Egbeda.

I call this ‘The Great Misalignment’: thinkers and systems builders think in one way – and the actual human beings, the doers and the beneficiaries of the systems, think in a completely different way. In that gap lies the frequent failure of policy, persuasion and the changing of norms.

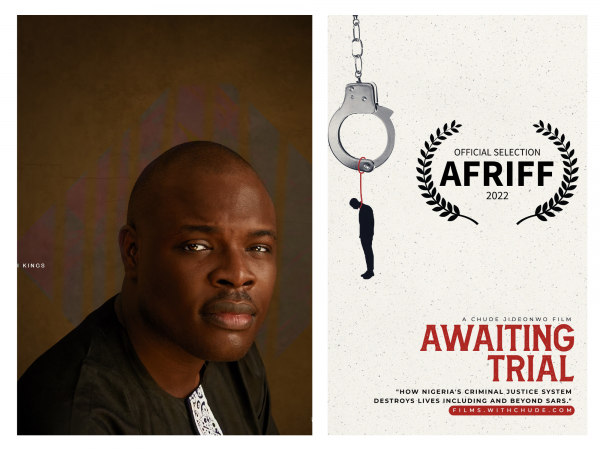

When people ask me how come my show #WithChude goes viral regularly and also ‘why do ‘people always cry on our show?’, I say it’s because people know when a thing is true to them, and made for them, and authentic to the way they think, feel and grow.

When a society hears itself, it shifts itself.

Unfortunately, in philanthropy, because of the point of view of the capital, from the World Bank to the UN and Rockefeller and Luminate – there is a gap between the builders of systems and the people those systems are meant to serve.

So NGOs, donors and researchers often build for behaviour that doesn’t even exist.

We say “empower women,” when people already have a way they empower women, and the Iyaloja’s cabinet is wondering what you are talking about with your latest non-equitable feminist theory.

We say “support local education,” and they wonder: are the Qur’an classes we have been doing all these years a joke to you?

We design campaigns for gender equity and youth inclusion, but we ignore the pulpit, the street corner, the skits, where people actually make sense of right and wrong.

The result?

A profound misalignment between capital and culture.

⸻

In the group of media and communication companies under RED | For Africa, which I co-founded 20 years ago this year, we built the TV show Church Culture on Channels TV and a consulting agency called Church Culture because we saw this missing gap and wanted to help local and global institutions close it.

To help shake decision makers free from their blind spots and false assumptions and help them follow the evidence: “Look at how people actually behave. Understand it, respect it, align your systems to it.”

It’s also the reason I decided to put my money where my mouth is for this thesis and launched the FourthMainland Creator fund to invest $500,000 of my own money in the future of independent media in the continent.

Because the misalignment is not about capacity.

It’s about point of view.

We have to change our point of view, from trying to build systems for Africans, to building systems from Africans.

When we design philanthropy in Africa through the gaze of Western institutions, or in reaction to them, we borrow their language and their anxieties.

We act for instance as if religion is a problem to be managed, not the most sophisticated institution on the continent.

We treat emotion as an obstacle, not the starting point of all human behaviour.

But if we want to help build African philanthropic organisms that will create change that lasts, this must change.

If you want to build lasting change, you must fund not just what people need, but what people believe.

We must design interventions that don’t try to ‘civilise’ our culture, but activate it.

We must start thinking from the ground up, not the outside in.

⸻

If we don’t fund stories that speak to how Africans actually live, pray, love, and argue, then we’ll keep funding reports about why our work never scales.

It doesn’t matter if you think there is something wrong with their taste in film or choice of faith, the reality is what it is. If you consider their choices stupid, then you must listen to the risk professor Nassim Nicholas Taleb, who writes in his book Skin in the Game that by definition, what works cannot be irrational. If something stupid works, it cannot be stupid.

He argues that what might appear illogical can be rational for survival in complex, real-world scenarios.”Survival comes first,” he says. “Truth, understanding, and science come later”.

This is what the postmodernist cool kids now call viewpoint epistemology, or standpoint theory – which, summarised here, essentially means you cannot successful design interventions without thoroughly understanding and accepting the point of view – and the way of life – of the people whose lives you claim you want to change.

Or as the OG changemaker, Jesus of Nazareth put it according to the Bible: Can any one enter a strong man’s house and plunder his goods, unless he first binds the strong man?

I believe this is the question that the African Philanthropy Forum has gathered us here to begin to answer today.

How do we fund films that move people without first judging their taste?

How do we engage religion with thoughtfulness and acknowledgement without secretly thinking people are wrong for how they practice their faith?

How do we get rich people across Africa to give away money in a way that is actually sustainable, in a way that achieves the most impact and the least damage, while at the same time helping them feel good about themselves?

It is of course a miracle, worthy of testimonies from the pulpits of The Lord’s Chosen ministries, that the Gates Foundation, birthed in materialist Western offices has been chosen …by God to help pioneer this conversation. But it is a welcome pivot, it is an important milestone. It is a pivot in POV.

A POV that now recognizes:

We will not build Africa by teaching Africans how to give.

We will not build Africa by telling Africans what to watch.

We will build it by recognizing why they already do what they do.

And then we will build systems, structure and solutions from the point of this acceptance.

The APF has already started the crucial work of changing the pattern asking textured questions that can truly transform how philanthropy can influence social norms across Nigeria and Africa.

May we – by the grace of God – together give these crucial questions the evidence-based answers they urgently require.

Thank you for your time.

And let the church say what? Amen.